Death Rally

Written by: Rik

Date posted: March 8, 2023

- Genre: Racing

- Developed by: Remedy

- Published by: Apogee

- Year released: 1996

- Our score: 7

Death Rally is one of those games that made more of an impression on me through its ubiquity on abandonware websites of the early 00s, when DOS games and small download sizes were very much the order of the day, rather than through contemporary reviews. With general vibes a mixture of Micro Machines 2 and Carmageddon, and a release date sandwiched somewhere between the two, at first glance it’s your typical mid-90s fare: top-down racing, but made more exciting by a futuristic setting in which everything has gone ke-razy with weapons, blood, and violence. Or, to put it another way, it’s not called Death Rally because its title offers a frank and honest assessment of the dangers inherent in driving a souped-up Citroën at high speed through rural Wales.

It also happens to be the debut effort of Finnish development team Remedy, who went on to make the excellent Max Payne games (and the good-ish Alan Wake), as well as having the distinction of being one of the final few games released under the Apogee name before the publisher became 3D Realms, with the latter initially being conceived as a brand for their 3D games, such as Terminal Velocity and Duke Nukem 3D, until it became obvious that pretty much all games were going to be in 3D for the foreseeable future.

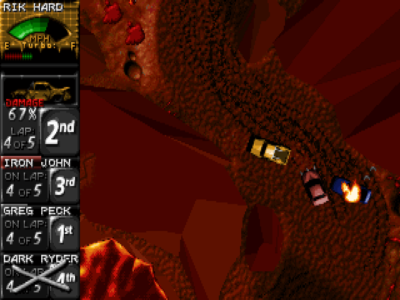

So Death Rally has a little bit of pedigree behind it, as well as a cameo from Duke himself, turning up late in the game as one of the tougher opponents (by which point you will likely have already superimposed personalities onto some of the more irritating mid-table blighters that recur in races during the meat of the game, and limited skirmishes with Duke, even if they are supplemented by occasional glimpses of his portrait and snippets of ‘Hail to the King, baby!’ are unlikely to dislodge any of them as top antagonist. Oh Dark Ryder, you utter prawn, why must you always shower my car with bullets?)

The basic building blocks of Death Rally will be fairly familiar to most: start at the bottom of a racing league, with a slow car, then race to win money and upgrade, and move up the table. It is, however, much more like a genuine racing league than the ‘lose once and you’re out’ or ‘slow death caused by constant cash flow problems’ favoured by some other similar games. You keep going, cycling through a series of races across a total of 19 tracks, until you reach the top, at which point you have the opportunity to battle an opponent called ‘Adversary’ for the ultimate title.

Game over is possible, if you happen to run out of money, which is equally possible, with purchasing choices and economic mismanagement still potential sources of peril until you get to grips with how it all works. Particular pressure points are when your car has been upgraded (engine, tyres, armour) to its maximum capacity and you decide to trade it in for a faster and beefier model, at which point you find out that the prices of upgrades and repairs have all gone up, and that your new car might not quite guarantee a level of performance in races to secure sufficient funds.

But a lot of the usual era-appropriate punishment mechanisms are absent: you can save between races, with a number of slots available, while you’re given a fair price for part-exchanging your old vehicle when upgrading (and fair warning of the sums involved before you proceed and confirm). Hell, at the start, the game will even warn you not to prematurely enter any of the more difficult races with your terrible starter car, if you try to do so.

Do you see what you get, Dark Ryder? Play with fire, you get burned. Oh, now you see… now you KNOW what it is that you get! When you mess with the big dogs, of which I am the biggest… [continues in this vein for 15 minutes or so]

Strategy comes into play mid-game when choosing a race. There are 20 racers but only 12 slots available in each round – 3 races with grids of 4, rated as easy, medium and hard (this is all separate from the general difficulty level – from 3 – that you choose at the outset). At various points, you have to factor in prize money, your likely repair bills and one-off upgrade costs, as well as the specifics of the opponents you will be up against. Not everyone will race each time, but if you eagerly jump the gun and put yourself in the hat for a hard race, your three opponents might all be top dogs with much better cars and equipment. You can always wait to see who goes first, but if you’re too slow you’ll miss out altogether, avoiding any costs, but losing the opportunity to win money and ranking points. In certain circumstances, though, deliberately skipping a round might still be the best option.

All of which requires that you take note of the different racers’ rankings and what car they happen to drive. Which you can soon commit to memory as you’ll see plenty of each of them through the constant cycle of races and, unlike you, they never change vehicle. If you finish last, get lapped by any opponent, or are destroyed, there’s no prize money; otherwise, a place in the top 3 will at least earn you something for your trouble. Avoiding any damage in a race, or finishing as the sole survivor, earns you a cash bonus.

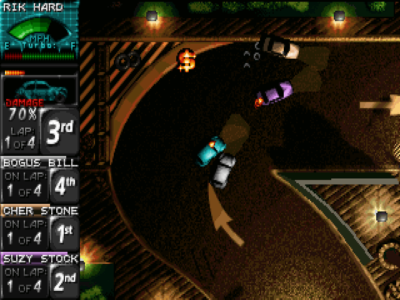

You can also secure extra money through on-track pickups (although these are forfeited in the same scenarios described above). Supplies of nitro, ammunition and repair bonuses are also readily available, and all three are often placed teasingly away from the optimum racing line, tempting you to risk your position. In place of the usual oil slick hazards, you have magic mushrooms, the effects of psychedelic drugs here (unsurprisingly) presented in the 1990s-tripping-balls-comedy-freakout tradition, rather than the more modern, middle-class Guardian reader, small-doses-treat-anxiety-actually interpretation. They, er, cause the screen to go a bit funny, making it harder to drive, is what I mean.

The racing itself is very good, particularly once you’ve repeated the tracks enough times to learn them and get used to the rhythms of the action, at which point saving time through mastery of corners, particularly on especially twisty courses, is rather satisfying. A handful of circuits make use of on-track speed boost sections, but other than that, it’s all refreshingly free of gimmicks. The impact of upgrades is immediately obvious out on the track, while combat is well-integrated, with damage incurred by weapons a real enough threat to all racers if ignored, but without being a dominant element of the action.

The only things that I didn’t feel quite worked were the occasional, randomised offers from third parties to pick up and deliver pills, or destroy a particular opponent in a race, in exchange for a cash bribe. Most times you end up getting distracted, and then have vague sounding threats made against you afterwards (at which point, re-loading a previous save seems fair enough). Similarly, using the in-game loan shark seems slightly unnecessary, unless you really take exception to making use of save games. I also never really found it worth my while to sabotage an opponent (reducing their armour at the start of the race, making them in theory easier to destroy) considering the fee involved, although on one or two occasions I did get lucky and benefit.

Otherwise, it’s all fairly enjoyable stuff, with the level of challenge only really cranked up to ‘slightly unfair’ during the final race with the Adversary, during which – on medium difficulty – I pretty much found I had to hit virtually every nitro pickup and avoid any driving mistakes in order to secure victory. If you lose and drop below the top position in the table (as others secure ranking points in league races to move above you) then you’ll have to get back up to the top again to get another go. (Or, as previously mentioned, re-load your save).

With pumping music punctuated by occasional spot effects and speech samples, the aesthetics of Death Rally occasionally call to mind a mid-90s pinball sim – in a good way. While I suspect at the time the in-game graphics seemed like a low-res disappointment after the shinier and sharper menus, it’s now the other way around, with the visual polish of the off-track segments now seeming a bit naff and lacking the character of the main action. Ditto the CG intro and cut-scenes, their inclusion perhaps necessitated by the times, but now exposed as visually dated and adding little of substance.

Some might be put off by the mid-game grind and the repetition of the same tracks over and over again, and find themselves asking the question, ‘does this racing league just go on and on forever until I win it?’ (The answer to which is, ‘yes, although the number of races it takes you to do it ultimately determines your final high score’). But I generally found Death Rally to be a much more engaging and well-implemented version of the hackneyed violent-future-racing clichés of the period, and as such, it comes with our warm recommendation.

Posts

Posts

Still one of my favourite racing games ever. I still remember always trying to win the race by just destroying every opponent (not sure but I think you received a bonus for that).

March 8, 2023 @ 9:54 am

You certainly get a bonus for being the last one left alive on the course, but I think that’s regardless of who dealt the killer blow in each case. Can’t recall ever destroying all 3 opponents myself, but would be surprised if it differentiates between the two scenarios.

March 8, 2023 @ 10:43 am