Crusader: No Remorse

Written by: Rik

Date posted: November 17, 2021

- Genre: Action

- Developed by: Origin Systems

- Published by: Electronic Arts

- Year released: 1995

- Our score: 7

Crusader: No Remorse occupies a strange place in my perception of gaming history, because it seems to have been released both earlier and later than I imagined. On the one hand, a big-budget 2D action game in 1995 seems, post-Doom, slightly passé and surely destined for failure; on the other, it also feels a bit too early for a fast-paced shooter featuring SVGA graphics throughout.

I guess that’s the answer: it was a period in which different approaches to getting around technological limitations needed to be actively considered and employed. In simple terms, by keeping to 2D, the resolution could go up. It’s a choice that’s dated pretty well, with time now judging the rush to 3D fairly harshly: I sometimes picture a different timeline in which the graphical style of Broken Sword, Toonstruck, The Curse of Monkey Island et al begat a whole range of other decent looking point and click adventures in the late 90s and early 00s instead of what was actually released during that period.

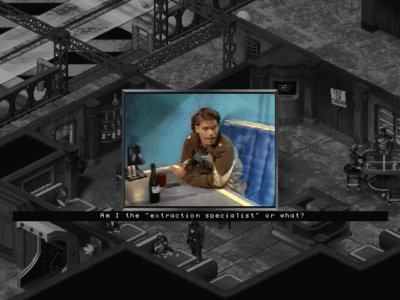

Anyway, speaking of 90s trends that were possibly jettisoned too early, Crusader also uses FMV cut scenes to tell its story, with various real actors dressing up in slightly daft outfits and posing in front of green screens in the name of providing you with some context for bursting into a series of rooms and blowing everything up.

Indeed, Crusader follows the lead of Origin stable mate Wing Commander in presenting itself like a movie, except in place of Chris Roberts’ name we have that of Tony Zurovec, who later went on to join Roberts at Digital Anvil and worked on an interesting looking open-world action game called Loose Cannon, which sadly never saw the light of day.

During the opening preamble, we are introduced to three red-suited stormtrooper types known as Silencers, whom we join mid-panic, having failed to assassinate some civilians that were mistaken for rebels. As it turns out, they are right to be worried, as two of the three are quickly gunned down by a big robot, before the third’s instinct for self-preservation kicks in, exacting swift revenge on the mech before escaping.

Such a turn of events leads your Silencer with little option but to abandon his former corporate employer, the World Economic Consortium: a global dictatorship established during tough times that now holds a grip over the population, with power concentrated in the wrinkly hands of old white men who sit around thinking of more ways to be evil. Fortunately, in time-honoured tradition, there’s a small resistance force to join up with instead.

Initial instruction comes direct from their leader, the ludicrously-attired General Maxis, with your first mission, like most of those that follow, involving the solo infiltration of a WEC facility. You’re told that an informant will meet you and give you an access card, but don’t wait for that first unarmed guy to give you one: he’s not an informant and will just go and set off the alarms (the actual meeting is mid-level). Turn it off and he won’t do it again, although you can follow your temptation to gun him down in revenge without any in-game consequences, if you’re so inclined.

The action is viewed from an isometric viewpoint, which always looks quite nice, but presents odd occasions when you can’t really see what’s going on. And unlike the protagonists of many action games, the Silencer can’t really move and fire at the same time, which takes a little getting used to. Instead, he can stand in a kind of macho shooting pose and shuffle backwards, or crouch and shoot, and he can spin around with his weapon drawn and spray bullets everywhere, but walking forward with your weapon drawn is a no-no. As a result, the action seems kind of stilted at first, and it can feel a bit like you’re trying to play X-COM or Jagged Alliance in real time, planning movements and actions quite deliberately rather than just relying on instinct.

However, although your correspondent felt it necessary to not only consult but print out the .pdf reference card in order to get a hang of the controls at first, it wasn’t long before it felt natural enough, with the traditional FPS combination of keyboard for movement and mouse for aiming feeling sufficiently comfortable and familiar the majority of the time.

Despite the slightly wooden movement and static-looking levels, a main selling point of the action is that many things can be destroyed, with the proliferation of explosive barrels making for some eye-catching scenes. While not massively impactful on how you approach things overall, with progress still barred by access to traditional keycards, force-fields and lifts, it’s quite refreshing to see scenery and bits of levels responding to a hail of gunfire rather than simply absorbing it. And at various points, there are even sections of wall that can be destroyed, and doing so is fairly satisfying, particularly when there’s an unsuspecting guard waiting on the other side.

Pickups are available in crates dotted around each level, as well as from the prone bodies of slain foes. A key incentive for searching bodies is stealing money which, for some reason, is required if you want to top up your supplies between levels, as the rebels require you to supply your own equipment. To do so, you need to visit a mercenary called Weasel during between-mission interludes at the rebel base.

Weasel’s acting performance is a slightly curious one that flits between camp and threatening, as you’re welcomed and enticed to peruse the merchandise in one breath before being chastised for wasting time in the next. That said, it is one of the more consistently entertaining segments of supplementary video on offer, particularly on your visits to the base, which gives the impression of being a hub with plenty to do when in fact you can only really speak to two or three other characters (including Weasel), or watch some WEC propaganda, in the bar, before you go and receive your next mission briefing.

In the main, your background as a tool of military suppression means that your distinctive red uniform is a less than welcome sight, so the others generally don’t like you, and the majority of exchanges are short and sharp. Along the way, as missions go a bit wrong, amid rumours of a traitor in the midst, things don’t really improve. In fact, it’s an altogether fairly downbeat story, although I won’t say too much more here (if you’ve played it, or don’t care about spoilers, see: Nice job, Tin Man! above).

Things get tougher as you progress, with the introduction of rocket-toting and mechanised enemies, both of which can make short work of you in open combat, and subtleties like making sure you avoid detection by security cameras (destroying them before they spot you is a good option) and deactivating alarms to stop a flow of guards increasingly become more important. Stealth is more a case of being a good idea than being actively enforced, even in the one mission where the briefing explicitly says that detection results in failure, while mistakes usually have temporary and solvable consequences – you can’t get into an irreversible situation where the whole base is alerted to your presence, and in most cases just turning the alarm off is enough to make everyone stand down. Guards don’t appear to be the brightest, in any case, and they won’t follow if you close a door behind you.

Hiding behind crates and walls to plan the next move is a recurring feature of the action, with the use of the Silencer’s ability to roll left and right to quickly break cover and take up a crouched shooting position rather satisfying to pull off. If done correctly, of course: the control scheme is such that I can’t really imagine anyone moving and rolling around a level in a slick and professional manner, although I guess it might be possible for the skilful and dexterous gamer. I kept getting my left and right mixed up and rolling into a wall.

Puzzles are largely limited to working your way around various traps, turning off security and getting through doors. There are sometimes numerous ways around a problem, which means that you can blunder or blast through some bits rather than doing something clever. That said, it can be quite satisfying to place explosives around a stationary mech and take it out before it becomes active, although not if you later find out it was one that you could control remotely via a nearby computer, and unleash hell on enemies with no risk to yourself. And sometimes you might pick up a keycard from a desk, then kill a guard and find he had the same one, implying that, on that occasion, you’ve taken a rather belt-and-braces approach.

Computers are otherwise useful for accessing security codes for doors with numeric locks (most messages are along the lines of, “For security, we’ve changed the codes and left them accessible to all via unattended workstations” or, “Dave, you forgot the code again?! Ok, this is the last time…”) or various initially humorous but eventually repetitive messages about the working environment at WEC.

I did draw a slightly sharp intake of breath when it looked as if jumping and platform-based navigation might become more significant, as neither seemed likely to play to the strengths of either the isometric viewpoint or the game engine. Crusader runs on a modified version of what powered Ultima VIII: Pagan, of which I have very few specific memories that were rekindled here, except when leaping rather stiffly, which took me back to an unhappy sequence in which Ultima’s Avatar was required to precision jump through some lava. Plus, there are some moving platforms featured: the perspective means it’s difficult to tell whether they’re on the ground or not, and you can also fall off them if you try to assume your combat stance while in transit.

These bits, as well as the imagined possibilities of getting lost in vast, confusing levels while contending with irritating lever-based puzzles were probably what put me off this game for so many years. But, I was wrong: fiddly bits are kept to a minimum, and it actually all flows rather nicely.

The only area where slight uncertainty prevails is around weapons and inventory. It’s almost a testament to how well Crusader has otherwise aged that you expect more of an in-game breakdown of how everything works and what it does, but this was the 90s, so you have to look it up in the manual (as with many games of the era, there are several supplements provided, some with information presented ‘in character’ along with various world-building elements). Even then, it’s not entirely clear whether it’s worth buying certain weapons or not and even at the otherwise forgiving lower difficulty levels, you won’t have so many credits you can just throw caution to the wind.

Management of shields is also a bit unclear: better batteries allow greater shield capacity, but in-game it is implied they aren’t a one-off upgrade (at Weasel’s store, I was told I didn’t possess a certain battery, when I definitely already did, and was invited to purchase it again). And there’s no overview of the inventory, you just have to cycle forward and back through it to look at/review what you have with you.

The story is a supporting narrative rather than a driving force for the action, and with Wing Commander III/IV in my head, I sort of forgot at first that their hefty video sequences were stored on multiple CDs rather than just one, and had to scale back my expectations accordingly. There’s just about enough variation in the levels, although cycling through similar office and industrial settings does get repetitive after a while.

The difficulty spikes quite a bit towards the end: I picked the second weediest of the four options (developers: always provide an odd number, so we cowardly and indecisive gamers can choose the middle one without too much agonising) and felt as if I was coasting a bit at times, with a surplus of medkits, ammo and energy cubes being left behind on levels. But ultimately, with multiple robots and respawning enemies to contend with, I was thankful not to have gone any tougher (and also for purchasing an EMP-type disabling gadget that temporarily confuses mechs). Incidentally, later opponents have a weapon that literally just melts your skin off, the sight of which, like the ‘setting someone on fire’ animations, may well have had the teenage me laughing and saying ‘Cool!’ in a Beavis and Butthead style, but now seems like the stuff of nightmares.

I’d probably had my fill by the end, and wasn’t in an immediate rush to hit up the sequel. But despite some initial awkwardness, Crusader: No Remorse is a surprisingly rollicking action game while it lasts, with awesome 90s tracker music that keeps the adrenaline pumping. Whenever you find yourself hunched over the keyboard’s quick save key, mouse claw firmly set, knowing you should do something else but finding an excuse for a few minutes more, it’s probably a sign of something pretty good.

Posts

Posts

You did the thing! Oleg will be pleased!

I played the first (and maybe second) Crusader on the PlayStation, where I imagine they were much more generous with auto-aiming. I guess one benefit of the stiff controls is that you didn’t NEED a mouse to get by.

But, yeah, it occupies surprisingly little of my memory. All I really remember of Remorse is spider-mining everything. All I remember of Regret is you could now freeze and shatter enemies. And then just a broad-stroke “yeah, those were okay” feeling for both. Big Wing Commander energy in the interlude sections, but I couldn’t describe a single character for you now. Consequences of a throwaway plot and similar levels, I suppose. Or just a bad memory.

November 19, 2021 @ 7:06 am

For once I actually did the thing instead of just talking about it, buying the game, and then getting distracted! I think it was in a GOG sale at the moment I realised I didn’t have the disc any more (still don’t understand why I kept No Regret but not this one, but there you go).

They must have simplified the controls for PSX somehow? I can’t imagine it with a joypad (although perhaps that’s what I tried on PC first time around, which must have been even worse).

The spider bots seem to be a fan favourite but I used them sparingly as I had a habit of blowing myself up with them. Possibly one downside of using the mouse to aim while fiddling around with the inventory.

November 19, 2021 @ 10:39 am

\m/ Ooh, yeah! \m/

(Headbangs. Fires up Paradise Lost – Sweetness. Headbangs a little more.)

Hi Rik,

Thank sfor this review!

As anticipated by J Man, I’m really pleased!

Frankly, from our last exchange of comments (on J Man’s hallowed ground, no less), I was afraid I’d pushed a little too hard on the subject, so at best, I would have expected an annoyed reaction from you, a ‘la Alan Rickman (RIP) , and a pun. (“Pfft … fanboys.”)

Anyway, here we are!

You know, I didn’t expect anything from this game. In fact, I wasn’t very attracted to his “tactical” pace, and the unusual controls bothered me a little. The game had remained untouched in my library for years, waiting for better times.

Then, I grew up and tried again, ending up returning to missions whenever I could, even if only for a few minutes – exactly as you wrote in the footnote.

In fact, if the game hadn’t attracted me so much, I wouldn’t have insisted. So, I’m glad you liked it, and in the end, maybe there’s one more reason: Warren Spector was the producer.

Now I’m playing the sequel, but had to stop to take some breath: they made it harder. And the jumping puzzles are more prominent, which is absurd, given that the game, at it’s core, was never intended as a platformer.

I think, I should try playing Wing Commander. I’d like the one with Mark Hamill, I think it was the third chapter. I’ve already seen it running on 3DO, back in the day when the console came out.

I remember seeing the movie with David Suchet, too, on VHS. It was passable (more of a teenage flick than a Space Opera), and I think the game is better.

Thanks again for giving me credit and for your beautiful writing!

Cheers,

Oleg

November 28, 2021 @ 12:25 am

“I think, I should try playing Wing Commander.”

That’s about J Man’s comment.

Despite the fact that the story tends to be negative, I kind of like it that way.

There doesn’t have to be a happy end, actually. The story may seem trivial, but somehow, there’s attachment, a sense of importance to what’s going on around you.

I remember that even the original Unreal left the protagonost drifting in space… until the Return to Na Pali.

In No Remorse, a good job was done, in my opinion.

November 28, 2021 @ 12:39 am

Greetings, Oleg!

There was no pushing on your part, as far as I could tell! Glad you enjoyed the review.

My hasty backpedalling in the JGR comments was more a recognition that the list of games I ‘always meant to try one day’ is long and though little things like reading reviews of similar games, or some positive encouragement, might take me in a certain direction, I was prepared for the fact that I might not follow through on that initial enthusiasm re: Crusader. I’m pretty sure there are historic comments from me elsewhere on JGR (and here) about possible future reviews that actually never happened…

When I first played No Remorse in the 90s I’m not sure I even went past the first level, so the signs weren’t good. But I was surprised how smooth progress was, once I got used to the controls, and by how much it drew me in.

So thanks for your recommendation! I definitely need a break before the sequel, but I do intend to play it sometime (perhaps setting myself up for another broken promise here, but still).

Would definitely recommend WCIII/IV. Been a long time since I played through them to completion, but blasted through the first few missions of III a few years ago and found nothing that spoiled my memories.

(P.S. Paradise Lost? There’s a blast from my 90s teenage past… and possibly for the other two FFG regulars too!)

November 29, 2021 @ 12:10 pm

Hi Rik,

Thanks for the clarification on Wing Commander.

I took WC III, now I will see how it works with me.

Cheers.

December 3, 2021 @ 12:19 pm