Quest for Glory I: So You Want To Be A Hero

Written by: Stoo

Date posted: March 1, 2006

- Genre: Adventure

- Developed by: Sierra

- Published by: Sierra

- Year released: 1992

- Our score: 6

If Rik and I ever run short on ideas for oldies to review, there’s always the Sierra back catalogue. With five main series of “Quest” adventures each providing between five and nine tiles, plus numerous other smaller families or one-offs, at one review a week each it would keep us going , oh (counts on fingers) between three and four months.

That’s unlikely to happen, mind you, as we’re both more Lucasarts fans. Plus Sierra brought us Lesuire Suit Larry, which I only ever played when I was 16 in the hope of seeing some boobs on screen, an experience I now look back on in shame. So don’t expect much coverage of that particular series. Still, we really should mention at least a few of the Sierra titles. Even if they did start to look a little tired and uninventive in the face of Lucasarts competition, Sierra did still bring us some solid quality adventuring. After all, they invented the genre in the first place.

This time around, we’re Questing For Glory, where the central theme is of an average nobody who becomes a great hero. This series was notable for using RPG style elements, such as fighting monsters, along with a set of character skills and numbers to determine what your hero can do and how good he is at it. If RPGs generally aren’t your cup of tea then you can at least rest assured it’s all fairly straightforward in execution. The first game was released in 1989, under the title Hero’s Quest which later had to be abandoned due to copyright issues. This review looks at the 1992 remake, which used a more advanced version of Sierra’s SCI interpreter. Apart from improved VGA graphics, that also means you get a mouse-driven point-and-click interface instead of wrestling with a text parser.

The game kicks off with your hero arriving at the small town of Spielburg, deep within a forest. He’s a blonde, cape-wareing sort with no real character or background; just an avatar for you the player. Spielburg meanwhile is a sleepy and picturesque sort of place in a quiet, forested corner of its medieval-based fantasy world. Farmers working their land, a jovial sheriff, honest townsfolk, a few shifty types, one or two more exotic residents, that sort of thing. Unfortunately, it has lately run into trouble. The ruling Baron’s children are missing, monsters stalk the forests and an evil witch lurks nearby. They need a hero to rescue them; with no better candidates around, looks like its up to you.

First you must choose the class of your hero – figher, magic user or thief. You then distribute a few points into various skills and attributes, although they’re already heavily weighted by that class choice. Once into the game proper, the main interface is pretty much the same as any other SCI adventure of the time – icons for walk, use, look, inventory, portraits for characters you’re talking to and so on. After a bit of exploring, however, you’ll learn the layout of GFQ’s world is a little different to the adventuring norm. Around the central town lies a large are of samey-looking forest screens which don’t contain puzzles, characters or anything plot-related. Rather, they’re an analogy to “wilderness” areas of an RPG, and here’s where you’ll find lots of random monster fights.

Combat is realtime; you face off against a single foe at a time and hit buttons to wave your sword around, cast a spell or dodge. How much of a beating your can take, and how much damage you can do are determined via character stats, RPG style. The fighter has the easiest time here; he’s the only one who can carry a sword and shield. The other two are stuck with daggers although the magic user of course has zappy spells. The thief is probably best at dodging, although I never quite got the hang of that myself.

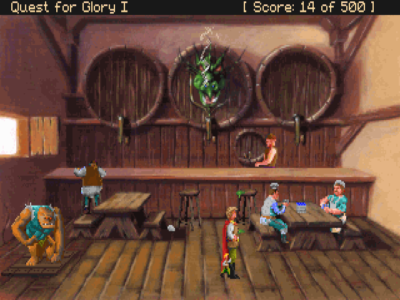

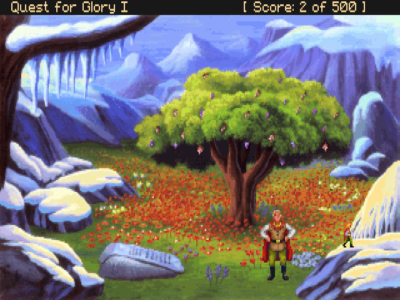

I had to go back years after writing and grab new screenshots… that’s why they’re all from the first five minutes of the game.

Dotted around the forest (and in the town) are locations where you can carry out activities other than hack-and-slashing monsters. Namely, talking to people and being sent on errands to find items. Highlights include meeting an eccentric hermit, finding food for a hungry ice-giant, and dancing with a bunch of slightly sinister fairies. There’s not exactly any “dialogue” though; you can question characters on various topics, and they’ll obligingly ramble on at length, but your own hero never actually appears to say anything. That’s back to him being a blank slate, a simple avatar for the player without any pre-determined character traits, which is common in many games but more unusual for an adventure.

The RPG attributes apply here too, outside of combat. For example, you get skills in climbing and lockpicking, and need stamina just to be able to run from A to B without collapsing. Often the skills provide more than one solution to a problem, which is something I always appreciate. At one point you need to retrieve a golden ring from a birds’ nest; you can either try to climb the tree or knock it down with a thrown rock. There is no system of character “levels”; skills simply improve with use. In fact it’s often worth practising just for the sake of it – better to spend a while falling out of a tree now, near the safety of the town, than find you’re stuck for lack of climbing skill later on. Use of these skills is often in place of traditional mental-dexterity problem solving you’d normally expect in an adventure, although the game is not completely without puzzles.

The game features the passing of time too, which I tend to be wary of in adventures as it can mean you get stuck when you miss timed events. In this case, there is one critical event which I (for reasons unknown) rarely manage to catch. There is a way past it, but only if your character can pick locks. Otherwise, as far as I can tell you’re pretty much screwed – but the game won’t tell you that, just let you keep playing on pointlessly. On the more positive side, the modelling of time brings with it a day-night cycle, which adds a little to the feel of an ongoing fantasy world. Your hero must carry provisions and sleep at night, and also shops shut, the town gates are locked and more dangerous monsters come out to play after dark.

Significantly, the game does play out differently depending on which hero type you pick. Fighters as mentioned have the easiest time in combat, but their downside is there are a few parts of the game they’ll never get to see. As the thief you can break into houses, and sell stuff at the local thieves’ guild, while the magic user can interact usefully with characters who are otherwise little more than amusing distractions. So there is that incentive to replay as another hero, to see what changes. You can actually try and create an all-rounder who can do everything, but the system is structured such that he would start the game painfully rubbish in every aspect, and require a lot of work to raise him up.

Overall it’s all fairly harmless lightweight fairy-tale stuff. It’s much like the series’ stablemate King’s Quest, just with added sword-waving. So it’s a bit twee, never entirely gripping, but mildly entertaining. I would say it’s family-friendly material, but then so were Lucasarts adventures despite often having a more anarchic edge. This is no equal of Monkey Island, to be sure, but it earns its place on the shelf of adventuring history, for its worthy attempt to do something a little different with the formula.

Posts

Posts