Need for Speed: ProStreet

Written by: Rik

Date posted: January 4, 2020

- Genre: Racing

- Developed by: EA Black Box

- Published by: Electronic Arts

- Year released: 2007

- Our score: 4

As much as I might like to position my ongoing attempts to cover the Need for Speed series as a heroic and epic struggle against the odds, I do of course accept that for the vast majority of gamers who are so inclined, acquiring and completing a Need for Speed game on an annual basis has proved to be easily within the bounds of possibility. It’s also, of course, how they were designed to be enjoyed: immediately after release and before the next one comes out. Still, here I am, an exhausted and bleary-eyed figure running towards you from a distance, gungey and ill-treated second-hand game box in one hand, a piece of paper containing some crudely daubed notes in the other, gasping for breath while forcing out the words, “Guys! It’s Need for Speed: ProStreet! I did it! I…got it working! Don’t go anywhere until I present you with a lengthy assessment of its merits!”

I’ll spare you the details, other than the actual solution (at the foot of this review), but suffice it to say that ProStreet was a bit of a sod to get working. Despite feigning indifference to this state of affairs elsewhere on the site, on the basis that the game’s reputation was less than stellar, in private it did of course drive me absolutely insane, and the period of experimentation testing out possible solutions was both lengthy and exhaustive.

At one point the only machine that seemed to run it was my puny laptop, with several graphical concessions, and I did consider proceeding on that basis and trying to make the best of it, while adding some kind of caveat about not being able to comment on the graphics (and/or also playing the Xbox 360 version – which I also bought – in parallel, for the purposes of benchmarking the visuals and handling against the at times rather rustic experience on PC). [I thought you said you were going to spare us the details? – FFG reader]

Anyway, for a brief period, buoyed by the euphoria of success in finally getting up and running, I was rather enjoying ProStreet, and I began to consider that the huffy contemporary reviews it received might have been a little harsh. Sadly, it was a feeling that was not to last, and my enthusiasm soured over many hours of grim and repetitive arcade racing to the extent that I not only felt that those 2007 reviews might have erred on the generous side, but also that playing the game was only marginally more entertaining than the experience of trying to get it to work.

Still, we are where we are. And speaking of which, in ProStreet, that place is now off the streets. Yeah, you’ve already got the respect on the streets, now it’s time to get the respect on the not-streets [Erh…you mean ‘the track’? – FFG reader]. Based on an assumption that the bit of The Fast and the Furious that everyone loved the most was the bit where they drive into the desert and conduct races in a controlled environment (and that was the best bit, definitely), ProStreet puts you in the shoes of Ryan Cooper, an ex-street racer now looking for more legitimate success as a driver. Bizarrely, given that they’ve bothered to name your character, there’s absolutely nothing else distinctive about him. That’s not a criticism of the characterisation: Ryan Cooper is literally just the name given to your mute avatar, who keeps his racing helmet on throughout and hence isn’t even given a face.

In fact, the story in general has been dialled back, along with the number of cut-scenes, while the camp video of the previous two games has been excised completely. The main storytelling device seems to be through the use of in-game announcers, supposedly compering each event and providing the crowd (and you) with updates on progress while adding in tidbits of character background. Unfortunately, like much of the action itself, it all gets a little repetitive after a while and you start to tune it out, while also being dimly aware of the fact an American (or – unexpectedly – a Geordie) accent has said the words “Ryan Cooper” about a million times since you were last paying attention. Occasionally a rival will be mentioned, or the game’s Big Bad Boss Man, Ryo (Ryan? Ryo? Ry-eally?) Watanabe, will pop up to slag you off over the PA system, or show up in person to intimidate you with aggressive wheelspins. He doesn’t have a specific beef with your character, other than he is currently ‘the best’ and you also want to be ‘the best’.

Clearly, proceedings will ultimately come to a head with a climactic series of races between Ryan and Ryo, but not before you first, in time-honoured tradition, plough through a career mode consisting of roughly a million similar races, beginning with a crap car and little money and ultimately ending with a souped-up selection of vehicles covering all available race types, adorned with lurid paint and vinyl/decal combinations of your choice.

You start with the standard lap-based race type, known here as Grip, and there are further sub-categories of race which are time-trial based, using either overall lap time or performance over individual sectors to determine the victor. While the roots of previous titles are immediately apparent, so too are the differences. This time, using an ability to bounce off solid surfaces without incurring damage or a significant time penalty is no longer an option, and collisions will bring a warning about the level of damage incurred as well as showing up on your car’s bodywork.

In addition, you’re also expected to make some concessions to genuine cornering technique, braking before turning, and maintaining the best racing line (as indicated by some helpful arrows on the asphalt). At first, this all seems rather refreshing: an attempt to do something a bit different with the series, addressing perhaps the low stakes of individual races in previous games and encouraging a more careful approach to driving and the treatment of your vehicles, with cash being required to pay for repairs in between races.

The problem, however, is that the forgiving damage model and gentle wide roads of previous Black Box titles were largely necessary to compensate for their vehicles’ rather woolly steering. There’d be bad moments, sure, but it all sort of hung together. In ProStreet, though, we have damage and tight corners but arguably even more ragged handling, which adds up to a frustrating experience where a smooth lap on certain tracks (particularly those with lots of walls and barriers) is virtually impossible. Compounding such issues is the placement of the chase camera, which often makes it difficult to see the road ahead of you, leaving you with a choice of switching to the first-person view or just sort of gritting your teeth and doing your best (I flitted between the two without finding a satisfactory solution) There’s also a weird juddery visual effect at high speed, which must have seemed like a good idea to someone at the time, but it also makes it harder to actually control the car with any precision. Braking is also less than responsive, with some occasionally agricultural pumping (oo-er) required to get your speed down with any urgency.

In mitigation against the large amounts of damage you’re certain to incur, you’re provided with minor and major damage ‘markers’ which you can use in place of cash for repairs, and can themselves be purchased in advance for a lower sum than the price of most repairs. Which all seems like an acceptance that the driving itself is actually flawed and isn’t able to stand up to the high stakes action that the structure itself seems to want to impose.

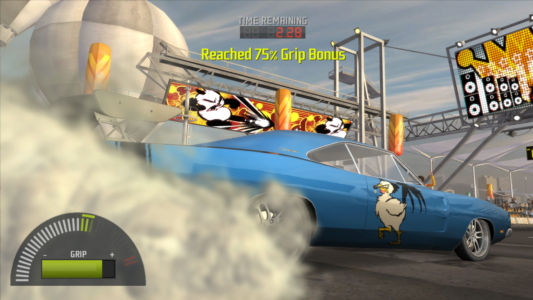

There are lots of options, but I chose the low-effort route when it came to my cars’ visual design. I couldn’t resist this picture of a chicken (a homage to Stroker Ace, no doubt) though.

Grip is but one of the available race modes, however, and none of the others are as afflicted to quite the same extent by these issues. Drag is similar to the similar events in previous NFS games, except with a mini-game at the outset based around heating up your tyres with a wheelspin. Otherwise, it’s mainly about managing your revs and gear changes, and handling issues are largely avoided, although when you get onto the more powerful beasts, even the slightest nudge of the steering can set you off on a path towards certain, race-ending destruction. (I should have said, the worst kind of damage is when your car is ‘Totaled!’ which is rather expensive, as you might expect, and needs a more substantial and pricey marker (or loads of cash) to rectify). It’s a best-of-three races affair, which sort of compensates for the brevity of each race but also serves to highlight its repetitive nature. Also, the blurry graphical sheen, and the unpredictable element of having to avoid traffic and other obstacles, were a big part of the appeal of the drag racing in previous games, and with both absent here, there doesn’t seem to be all that much to it.

Drift has also been repurposed from previous Underground-era titles, and it remains an imprecise art, with big scores often achieved through luck rather than skill, and sometimes in spite of said drifts being accomplished while being pinned to a trackside wall. Again it’s a best-of-three event, which means that by attempt three the impressiveness of any swish moves is likely to be undermined by the fact that your vehicle appears to be on the verge of falling apart. On a more serious note, the visual indicators from previous games that gave you more detailed feedback regarding how you are actually scoring points is missing here, which seems to be a retrograde step.

The one new and vaguely original race type is Speed, during which (logically enough) you are supposed to keep your top speed as high as possible. To this end, the courses are largely straight, with gentle curves that can be negotiated with little need for the brakes, and hence many of the issues that afflict the Grip races are bypassed. Many, but not all: using the chase camera is extremely hazardous here, and a permanent switch to first-person is necessary to help avoid multiple race-ending prangs. Although early Speed challenges are fairly uninspiring, a combination of the danger element (particularly on the precarious Nevada desert courses) and the slightly scarier camera angle, ensure that these events provide ProStreet‘s more exciting moments.

The meat of the career mode is based around so-called Race Days, in which performance is measured across a number of different races and, potentially, race types. You’re given a reward for supposedly ‘winning’ (doing well in some events) but what you really need to do is ‘Dominate’ (not winning every event necessarily, just doing a bit better, more consistently, across more events). And so, in a classic piece of EA rebranding, in which ordinary features and concepts are given exciting-sounding names as if that somehow changed their meaning, ‘winning’ an event doesn’t really mean winning it; and ‘Dominating'(tm) is the new name for *actually* winning. You can exit after ‘winning’, and you may well unlock other events, but the day will still show as incomplete on the career map. Occasionally, you’ll get to a more significant event, at which you’ll be rewarded with a big hunk of cash and a new car, and then eventually you’ll enter the endgame, in which you’ll need to face off against and defeat so-called Street Kings with expertise in each discipline, before final showdown with the, ahem, Showdown King, Ryo.

Previous games’ excuses for undertaking billions of races in career mode have stretched credulity somewhat, but there was more of an attempt to keep things on track than we seem to have here. At least the action all took place within a set environment (usually, a fake US city): here, the events seem to take place on tracks all over the world, but with little explanation as to why you’re in Germany one minute, Texas the next and Japan the other. Again, it only serves to highlight the repetitive nature of the action, as tracks are cycled through and repeated with no explanation.

Other than managing your car’s damage, there’s also the process of acquiring and tuning cars for each race type. Personally, I rather like the idea of having a collection of cars with different strengths (a la Test Drive Unlimited) but somehow ProStreet manages to make this area of the game as tedious and annoying as possible. I think it essentially boils down to the fact that the information you’re given about the stock vehicles that you can buy is basically meaningless and you’re given no clue as to the events for which they might be best suited, how you might tune then up, and – particularly – whether you’re actually going to like driving them when you’re out on the track. Make a wrong call and you’ll have ploughed thousands of dollars into something you can’t drive, and will get totally screwed on the resale value. There’s also an element of the game auto-balancing your opponents, too, so if you keep a shite car for a while the AI will be relatively easy to overcome, but if you have a more powerful one, there’ll be some dangerous opposition on the grid.

None of these issues are entirely new to the series, of course, but in the context of ProStreet‘s attempts at being a more serious and simulation-aimed affair, it just seems wrong that the wealth of information you’re given here is almost totally redundant, rendering this side of the game rather baffling and tiresome. And ultimately, a lot of ProStreet‘s problems do come down to trying to shoehorn the previous Black Box games into a format that doesn’t play to their strengths and only serves to highlight their weaknesses. The end result is a substandard and unexciting affair that lags behind the likes of TOCA Race Driver, a significantly older game, in terms of what it’s trying to do (right down to featuring a protagonist called Ryan).

While the equally poorly-received Need for Speed: Undercover wasn’t a strong effort and largely failed in terms of returning to the series’ Most Wanted-era heights, it didn’t frustrate and annoy me to quite the same extent as ProStreet does. So, while acknowledging that ProStreet shares a lot of DNA with better entries in the series, (and it does still look – and sound – pretty good), it has to be said that this is a weak effort overall, and probably one for series completists only.

Posts

Posts

Hi Rik,

You say that you had your back aking for trying to make it run on PC… have to report you bad news: I tried to make it run on PS2, but it didn’t work.

I bought an absolutely new, shop-fresh disk, but the game failed to run.

I went to the shop and asked to change it to another packed, new copy…I had a new copy, but still, nothing!

Guess, they’ve rushed it on theshelves. I remember that Carbon had issues too, so the story repeats here.

Though, I’m glad that I didn’t have to waste my time on it: TOCA Race Driver 2 had my attention, but I still have to finish it.

My overall opinion is, EA rushes out some really bad burgers, lately. We should try to avoid them.

Cheers.

January 26, 2020 @ 1:01 am

Hi Oleg!

Strange that the console version had issues.

PC NFS: Carbon may well be fussy too: I was still using Win XP when I played that last. Planning to give it another go soon though, so I hope it doesn’t turn into a big palaver like this one did.

January 27, 2020 @ 10:43 pm

I’m glad to hear that other people had issues with ProStreet as well.

While playing this on the Xbox 360, had no technical issues, I had a love hate relationship with the game. I love discovering the right car with the right tuning depending on the race type. The game also looks and sounds good as well. I also love that Ryan Cooper wears his helmet in all the cut scenes (I wonder if he keeps it on while doing mundane things like washing the dishes, taking a shower, being intimate with one of the race girls, etc. im sure he’s a nice guy under the helmet)

Now to the crap. Managing your damage levels so that your car doesn’t become scrap. The game is a slog to advance to begin with. If you’re spending money on repairs and markers (ha!), then it’ll take even longer to save for parts and other cars to complete the game. The selection of EA Trax (double ha!) during racing I find weak compared to previous entries ( specifically Underground 1&2). Overall, ProStreet can’t decide whether it wants to be a sim or arcade racer, hence my wishy washy feeling on this game. I find the driving in this game (s)hit or miss.

June 8, 2023 @ 4:32 pm