Midwinter

Written by: Rik

Date posted: March 10, 2013

- Genre: Strategy

- Developed by: Maelstrom Games

- Published by: Rainbird

- Year released: 1990

- Our score: 8

Midwinter was one of my favourite games to play as a youth. I didn’t really play it properly, though: in fact, most of its many subtleties were totally lost on me, and the majority of my time was spent skiing around randomly until something terrible – usually a fall, and a broken leg – transpired. When the game’s creator, Mike Singleton, recently succumbed to cancer, I felt strongly inclined to add a review to FFG, but was reluctant to do so on the basis that I’d never really experienced the game as intended. The best I would have been able to come up with was some vaguely positive remarks about Midwinter‘s open-world nature and the freedom it afforded the player – and while such thoughts would have been perfectly valid, I felt it deserved something more than hollow platitudes based upon fading memories. So, I decided to take some time to do it justice, play it to the end, with ‘baddies’ turned up to maximum, in order to offer something a little more constructive.

So: in Midwinter, the year is 2099. Sixty years have passed since the earth was stuck by a meteorite, triggering a second ice-age, and sending the world’s population scrambling for warmer climes. In the North Atlantic Ocean, west of the Portuguese coast, a small community has settled on Midwinter Isle, living a peaceful and comfortable existence, despite the sub-zero temperatures. When Midwinter’s radio communications are cut off, amid tales of unrest in the south-east corner of the island, Captain John Stark, leader of Midwinter’s Free Villages Police Force, is left to mobilise resistance.

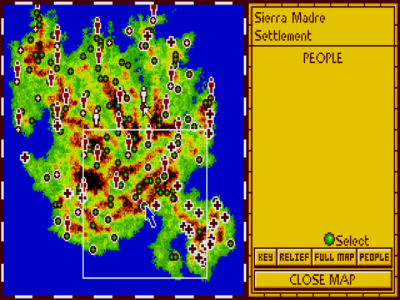

Midwinter Isle. Your squad are in white, potential recruits are in red, and the ominous-looking crosses are enemy units.

As you might have guessed, in the game, you are Stark, armed initially with nothing but a pair of skis and a sniper rifle, and the knowledge that the enemy, led by the nefarious General Masters, has already made significant progress in their campaign to conquer the island. As Stark, the first thing you need to do is escape the attentions of a nearby enemy unit. This is your first glimpse of Midwinter‘s so-called ‘Action Mode’, used for travelling and combat. You need to ski away from enemy vehicles and take them out with your sniper rifle, or evade their attacks until you make it to the nearest settlement.

Once you overcome these initial difficulties, you’ll need to take some time to study a map of the island and assess your situation. The enemy are advancing and hold several settlements already. The key to the campaign is Midwinter’s ‘heat mines’, the island’s source of power: once General Masters has captured all of these, the battle (and the game) is over. You can slow down the advance by sabotaging enemy held factories, warehouses and synthesis plants, or indeed by taking on enemy units directly.

You can also ask for assistance from other islanders – there are 32 in all. At the beginning of the game, the enemy is jamming the island’s radio communications and so Stark cannot call for help remotely. Instead, recruitment has to be handled face-to-face. The twist is, of course, that not all of the islanders get along with Stark, or each other, and their different personalities and prejudices have to be taken into account. Some characters are fairly easy going and can be recruited by almost anyone, while others are more difficult and need one of their close friends to ask them in order for them to join. Each character has a mini-biography in the game’s manual, which should be studied closely when planning a recruitment strategy. Inevitably, perhaps, the most useful characters are often the most difficult: Professsor Kristiansen, for example, has the ability to override the enemy’s jamming signal and recruit four characters (if you can get him to a radio station) but he won’t join unless one of a select group of other characters asks him.

A mishap while travelling prompts a neat little animation, accompanied by the sound of things falling into snow. This one brings back some memories.

Recruiting another character adds a turn-based dimension to the gameplay. You take direct control over each member of your team for two hours of game time; once the time’s up, or there’s nothing else to do, you switch to the next one. When you’ve done everything you can with each character, you then ‘synchronize watches’ to end your turn, at which point you’ll be presented with a summary of how each side is doing – how many heat mines are held by the enemy, how many enemy buildings and vehicles you’ve destroyed, and so on – and then you’re free to go again.

The great beauty of Midwinter is that you’re free to approach this task however you like, and you can eschew contact with other characters altogether, if you so wish (especially if, like the 10-year old me, you’re only interested in inflicting damage to Stark’s body by making him ski into the side of a house). However, recruiting other characters certainly allows you to get more done, and by sending your various team members to different areas of the island, tasked with specific objectives, you really start to feel as if you’re planning a guerrilla campaign, with many hours spent poring over the map screen plotting your next few moves.

Plotting your moves is one thing, but in Midwinter, you also have to execute them too. A great deal of your time will be spent (in ‘Action Mode’) traversing the frozen landscape, journeying from one settlement to the next. Skiing is your only option at first, and it’s a fairly treacherous affair: flat plains mean your energy will be sapped pretty quickly; hills increase your chances of building speed, but also carry significant ‘falling over and breaking your leg’ dangers. On top of all that, you’re also extremely vulnerable to attack from enemy units, mortar attacks guided by spotter planes, or planes that bomb you directly. You can always pause to try and take aim at foes with your sniper rifle, although this does leave your enemies with a stationary target.

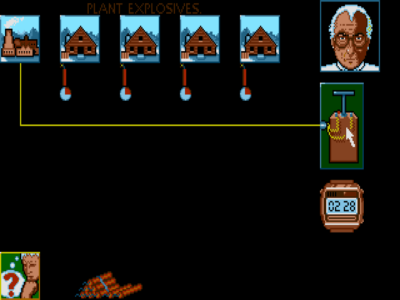

Sabotaging an enemy-held building. The picture of dynamite at the bottom of the screen is representative of the actual number of sticks you have. (Wow! Amazing! – a reader)

Finding a settlement with a garage will allow you to make use of one of a variety of snow-mobiles. There are minor variations in terms of top speed, passenger capacity, and offensive capabilities, but in most respects the Snow-Fox, Snow-Cat and Snow-Wolf are largely identical. All allow you make significant and speedy progress, especially across flat terrain, and all come equipped with ground-air missiles, useful for blasting enemy planes out of the sky (there are ground missiles, too, should you decide to go head-to-head with enemy ground units), so they should certainly be your preferred method of transport. The only downsides are that they don’t handle more mountainous terrain too well, and once you crash a snow-mobile, that’s it: no damage, no repairs, it’s just gone – you’re back to skis until you can find another garage.

Midwinter‘s most mountainous peaks can usually be accessed via cable-car, which is undoubtedly the safest form of transport available: you can’t be attacked when travelling, and your character can also rest during the journey. Unfortunately, cable-cars are usually only accessed at the bottom or at the top of a very big hill, so you don’t often get very far this way. Once you reach the top station, though, you have the option to hang-glide, and this can be a fairly effective way of travelling significant distances, although you still need to evade the attentions of enemy planes, and crashing carries a significant injury risk.

Depending on the length and distance of your journey, and your chosen method of transport, your character may tire and be in need of rest before the next turn. Most settlements have buildings – usually houses – that allow you to use remaining time to eat or sleep and recoup much-needed energy before the next situation report. Some settlements will have a magazine, allowing you to re-stock with dynamite (required for performing sabotage) or replenish your snow-mobile’s missiles. Local stores also (bizarrely) usually stock a limited supply of dynamite, too. You can refuel your snow-mobile at a garage, while churches and bunkers both provide a level of cover for defensive sniping. Factories, synthesis plants and warehouses are generally for sabotage only – certainly if they’re already in the hands of the enemy, although blowing them up anyway can’t hurt – it just stops them being captured in the first place.

It’s all pretty compelling stuff. Given Midwinter‘s age, you might reasonably expect the action sequences to be fairly terrible, but in actual fact, they stand up rather well. The polygon graphics are pretty simple and the animation kind of lumpy and lurchy, but it certainly remains an effective representation of a bleak and featureless frozen landscape. Such is the focus on covering distance and getting to the next settlement, it can be tempting, particularly when travelling by snow-mobile, to spend the majority of your time squinting at the mini-map rather than the main display, but you take your eye of the terrain at your peril, lest you allow your vehicle to overturn in a shallow divot.

Combat largely takes care of itself, and missiles find their target with minimal aiming required – the challenge in taking on enemy ground units is in the sheer numbers you have to deal with: there could be 50-60 vehicles in any particular unit, and unless (by happy chance) you happen to take down the unit leader – at which point, the unit surrenders – you’re going to have to defeat around 30 units without reply in order to win each battle. Such overwhelming odds are in keeping with the general theme of being under attack and conducting a defensive campaign, though, and it has to be said that the dreaded buzzing of nearby enemy engines, especially given the paucity of other sound effects, causes the requisite amount of dread, alarm and panic as the player anticipates the battle ahead. Pulling off victory under such circumstances can be a genuine punch-the-air moment, especially if by doing so you manage to keep a heat-mine out of enemy hands for a little longer.

As we mentioned, though, much of the joy in Midwinter is in gazing over the map and planning your next move. If and when you manage to recruit a significant number of team members, you can send them to the different corners of the island, and this helps to keep things interesting. With each turn, a little more is achieved for each individual or team, and you certainly find yourself investing in each mini-quest, finding excuses to have just one more turn so you can get to the next settlement and recruit another character or blow up an enemy factory. Indeed, by the time I approached final victory, I was reluctant to follow through and end the game while there were still so many other little stories elsewhere on the island still to be completed.

Even as I write these words of warm recommendation, there remains a nagging feeling that I might be giving away too much, as a great deal of the enjoyment in Midwinter comes from the freedom to work things out for yourself. The same goes for criticisms – to get too specific about some of the game’s mechanics would be to spoil some of the game itself, so I’ll try my best to keep this brief also. One very general point to make would be that it helps to see Midwinter as a game, with rules, rather than constantly asking logistical questions, such as, “How can General Masters sustain such a significant fleet of aircraft?” and “Why would the enemy ignore members of your team present in an enemy held settlement, just because they’re hiding in civilian buildings?” or “How can it be possible to blow up an enemy building with a simple click of a button?” – all valid points but, well, that’s just the way it is. You don’t ask why a bishop can only move diagonally in chess.

Elsewhere, despite the interface making use of symbols (which I usually find baffling and is a bit of a pet hate of mine) it all seems to work well enough – mainly because there aren’t all that many to deal with in the first place. There are one or two quirks, though. The only way to check whether your character is carrying dynamite is to stop at a settlement and see whether the sabotage option appears, and there’s no way to pass dynamite from one character to another, even if they’re travelling together or in the same place. Speaking of travelling together, things can get a little bit confusing when one of a group exits a snowmobile and it then seems to disappear (it hasn’t, but you need to click around a bit to find which character it’s attached itself to). There are similar problems when you arrive at a settlement with a garage and there are two snowmobiles at the same settlement – no bugs, nothing’s broken, and it can be worked out, but it can get a bit fiddly.

A final point relates to the difficulty: I won’t say too much, and it’s certainly not an easy game, but suffice to say that using some methods are more likely to bring about victory than others, and when I managed to finally sabotage General Masters’ HQ at Shining Hollow, the ease with which such a task was accomplished took me slightly by surprise. Set against that, though, is the fact that I had enjoyed many, many hours of play before getting to that stage, and it could well be that some of my previous knowledge had been more beneficial than I’d realised. Still, I’d recommend turning the difficulty up by switching mortars and bombers on at the start (you’re likely to be cursing them throughout, mind you).

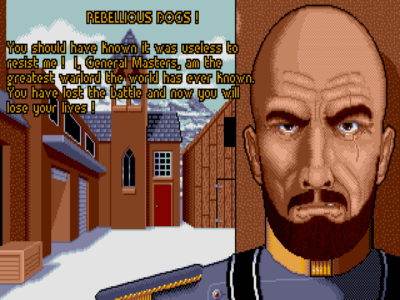

If things look bleak, you can surrender to General Masters, although you may as well just quit and restart. Unless you particularly enjoy being called a rebellious dog.

My overall assessment is that Midwinter remains rather enjoyable. It’s difficult to eradicate nostalgia and historical fondness from the equation: while I may have been playing it ‘properly’ for the first time, the many hours I spent with it as a youngster can’t be discounted (sad fact: the copy protection screen for Midwinter requires you to identify two of the islanders by their pictures – as a kid, I memorised all the names and faces so I didn’t even have to look at the manual). Many oldies fall into this category, though, and despite them retaining some entertainment value, they can often seem like hard work in places. Not only was that not the case with Midwinter, after several hours’ play it had reached the part of my brain that made me think about my strategies while I was at work, in the shower, or trying to go to sleep. To be honest, that’s a rare thing these days.

And that’s without even taking into account all that stuff about how ambitious and how much of an achievement-for-its-time Midwinter was and is. But, yes, all that stuff too: it’s less than 1MB big, for goodness’ sake – you could put it on a floppy disk and play it straight from there (if you could find a disk and/or a PC with a disk drive, of course). Mainly, though, it’s just a really good game. I can’t guarantee that some won’t find it baffling and unforgiving, but, whether you sort-of-remember it or not, it’s definitely worth some of your time finding out one way or the other.

Posts

Posts

I missed this review’s original publish somehow – looks pretty brilliant! Did you ever play Dune? (Not Westwood’s RTS, the one from Cryo I believe) Some of the guerilla campaign management sounds similar, but with a more free polygon world.

December 31, 2013 @ 8:52 pm

I never tried the first Dune game, although I have dim memories of watching someone else play it.

This kind of thing isn’t normally my cup of tea – I’m not sure whether I discovered a new level of interest and competence while playing Midwinter, or if my progress was fuelled mainly by nostalgia.

Certainly, the sequel, Flames of Freedom, remains a daunting prospect – and one that I’m in two minds about tackling.

January 1, 2014 @ 4:30 pm

Thanks for the awesome nostalgia trip, I loved Midwinter when I was a kid and played it far too much. Can’t wait for the remake due in 2015, it’s looking good.

February 13, 2014 @ 8:59 pm